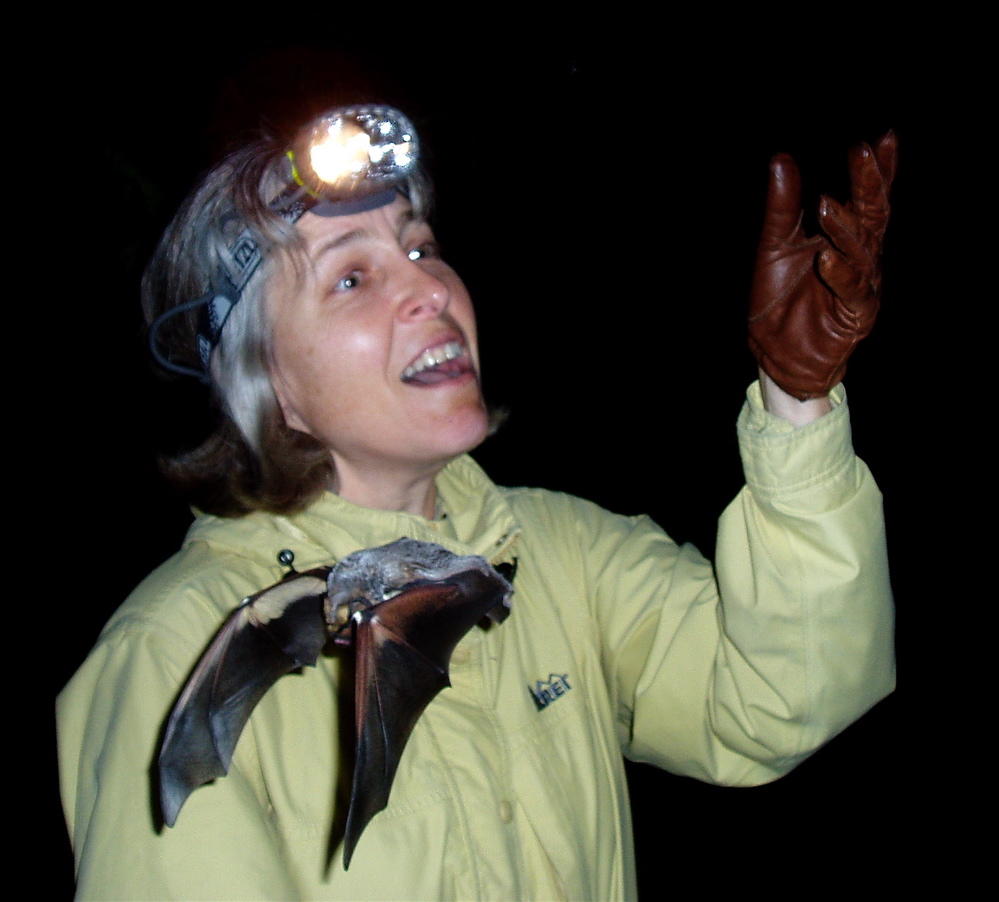

Ardops Nichollsi

The bats in the Caribbean are mostly very different from the ones we have here in North America. Many of them are leaf-nosed bats, Phyllostomids if you speak Latin, like the bats I saw in the Yucatan. This little teddy bear of a bat was classified as a "reproductive male" for reasons which are pretty obvious although some of them were even more alarmingly obvious.

On St. Lucia, not all the bats got released. The team had permits to "take" a certain number of each species. We knew each night how many of each species were to be kept, and the kept bats stayed in their bags until the next morning, when they were humanely euthanized and then "processed" more completely. This meant that tissue samples were taken for genetic analysis, and then they were preserved in formalin and taken back to become museum samples.

The good part of this is that future researchers can examine the bats for reasons we don't even know yet, and in the dreadful event that they go locally extinct, for example due to climate change, there will be a record of what they were. Only bats that are fairly common are taken, so it probably has little affect on the survival of the population.

The bad part is that we're all doing this work because we love bats, and so it's super hard to see them killed. This work is not for me, but I will not speak badly of those who do it.